F. Mathias Alexander writes about the importance of foot use, and placement, several times on Man’s Supreme Inheritance (MSI) and in The Use of the Self (UOS). (There are also 4 references to feet in Constructive Conscious Control and another 4 references in The Universal Constant. However those references do not deal with foot use.)

For the most part, foot use has not been given a lot of attention in Alexander Technique teaching, despite several quotes indicating that Alexander felt it was of crucial importance. This may now be changing as the two videos at the bottom of this page suggest.

Here are a few key quotes from MSI and UOS that show just how important foot use was in Alexander’s thinking. Below these quotes, you’ll find all the quotes relating to foot use in both books.

...it will be quite evident that the primary principle involved in attaining a correct standing position is the placing of the feet in that position which will ensure their greatest effect as base, pivot, and fulcrum, and thereby throw the limbs and trunk into that pose in which they may be correctly influenced and aided by the force of gravity. – MSI

…I continued with the aid of mirrors to observe the use of myself more carefully than ever, and came to realize that what I was doing with my legs, feet, and toes when standing to recite was exerting a most harmful general influence upon the use of myself throughout my organism. This convinced me that the use of these parts involved an abnormal amount of muscle tension and was indirectly associated with my throat trouble, and I was strengthened in this conviction when I reminded myself that my teacher had found it necessary in the past to try to improve my way of standing in order to get better results in my reciting. It gradually dawned upon me that the wrong way I was using myself when I thought I was ” taking hold of the floor with my feet ” was the same wrong way I was using myself when in reciting I pulled my head back, depressed my larynx, etc., and that this wrong way of using myself constituted a combined wrong use of the whole of my physical-mental mechanisms. I then realized that this was the use which I habitually brought into play for all my activities, that it was what I may call the ” habitual use ” of myself, and that my desire to recite, like any other stimulus to activity, would inevitably cause this habitual wrong use to come into play and dominate any attempt I might be making to employ a better use of myself in reciting. – UOS

The stimulus to employ the new use of the head and neck was therefore bound to be weak as compared with the stimulus to employ the wrong habitual use of the feet and legs which had become familiar through being cultivated in the act of reciting. – UOS

Man’s Supreme Inheritance (1946 reprinting):

“I think the average man is very apt to forget that he cannot assume a position of stable equilibrium and a position which ensures a perfect mobility, unless his feet are so placed as to furnish at once a stable pose and a ready pivot and fulcrum.

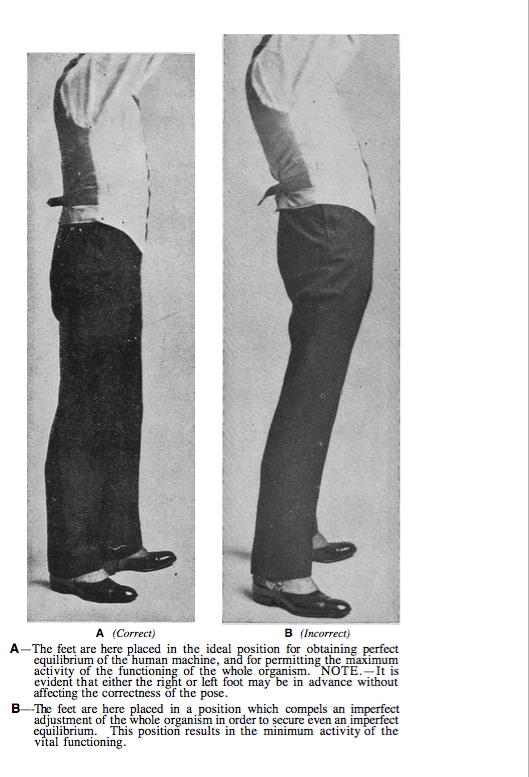

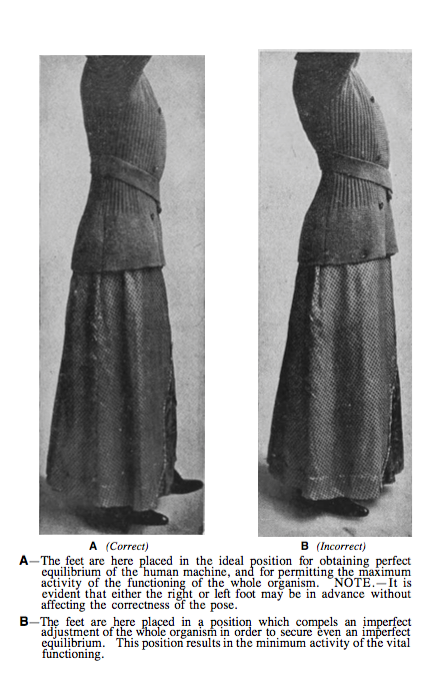

“The most perfect base is obtained by setting the feet at an angle of about forty-five degrees to one another. In all other erect positions (the defects becoming exaggerated as this angle is decreased) it will be found that there is a tendency to hollow and shorten the back and to protrude the stomach, and if any effort is made to avoid these serious faults in posture, such effort will only result—unless the feet are moved to the correct position—in a stiffened, uneasy, and unstable attitude. It is not possible, however, to set out in written language the correct pose of the feet and legs in the ideal standing position, and I therefore subjoin four photographs which have been specially taken for this purpose (first published on 22nd October, 1910), and which show quite clearly not only the correct position of the feet, the fundamental problem, but also how the whole body of the person is thereby thrown into gear.” – pages 164-65

“From what I have now said, it will be quite evident that the primary principle involved in attaining a correct standing position is the placing of the feet in that position which will ensure their greatest effect as base, pivot, and fulcrum, and thereby throw the limbs and trunk into that pose in which they may be correctly influenced and aided by the force of gravity. The weight of the body, it should be noted (see diagram AA), rests chiefly upon the rear foot, and the hips should be allowed to go back as far as is possible without altering the balance effected by the position of the feet, and without deliberately throwing the body forward. This movement starts at the ankle, and affects particularly the joints of the ankles and the hips. When inclining the body forward, there must be no bending of the spine or neck; from the hips upwards the relative positions of all parts of the torso must remain unchanged. When the position is assumed, it is further necessary for each person to bring about the proper lengthening of the spine and the adequate widening of the back. The latter needs due psycho-physical training such as is referred to in the two extracts quoted above. This standing position as now explained is physiologically correct as a primary factor in the act of walking. The weight is thrown largely upon the rear foot, and thus enables the other knee to be bent and the forward foot to be lifted; at the same time the ankle of the rear foot should be bent so that the whole body is inclined slightly forward, thus allowing the propelling force of gravitation to be brought into play.” – pages 167-68

“These same rules are equally applicable in principle to the acts of sitting and of rising from a sitting position. Very few people have the right mental conception of the “means whereby ” of these acts or of the correct use of the parts which should be employed in their performance, and this despite the fact that we are performing these acts continually, and with such apparent ease from our own point of view. If you ask any of your friends to sit down, you will notice, if you observe their actions closely, that in nearly all cases there is undue increase of muscular tension in the body and lower limbs; in many cases the arms are actually employed. As a rule, however, the most striking action is the alteration in the position of the head, which is thrown back, whilst the neck is stiffened and shortened. Now I will describe the correct method, but it must be borne in mind that it is useless to give what I here call ” orders ” to the muscular mechanism, until the original habit and the principle of mental conception connected with this action have been eradicated. If, for instance, before giving any of the ” orders ” which follow, the experimenter has already fixed in his mind that he is to go through the performance of sitting down, as that performance is known to him, this suggestion will at once call into play all the old vicious co-ordinations, and the new orders will never influence the mechanisms to which they are directed, because those mechanisms will already be imperfectly employed, and will be held in their old routine by the force of the familiar suggestion. Firstly, then, rid the mind of the idea of sitting down, and consider the exercise and each order independently of the final consequence they entail. In other words, study the ” means,” not the “end.” Secondly, stand in the position already described as the correct standing position, with the back of the legs almost touching the seat of the chair. Thirdly, order the neck to relax, and at the same time order the head forward and up. (Note that to ” order ” the muscles of the neck to relax does not mean ” allow the head to fall forward on the chest.” The order suggested is merely a mental preventive to the erroneous preconceived idea.) Fourthly, keep clearly in the mind the general idea of the lengthening of the body which is a direct consequence of the third series of orders. And fifthly, order simultaneously the hips to move backwards and the knees to bend, the knees and hip-joints acting as hinges. During this act a mental order must be given to widen the back. When this order is fulfilled, the experimenter will find himself sitting in the chair. But he is not yet upright, for the body will be inclined forward, unless he frustrates the whole performance at this point by giving his old orders to come to an upright position. Sixthly, then—and this is of great importance— pause for an instant in the position in which you will fall into the chair if the earlier instructions have been correctly followed, and then, after ordering the neck to relax and the head forward and up, the spine to lengthen, and the back to widen, come back into the chair and to an upright position by using the hips as a hinge, and without shortening the back, stiffening the neck, or throwing up the head.

“The act of rising is merely a reversal of the foregoing. Draw the feet back so that one is slightly under the seat of the chair, allow the body to move forward from the hips, always keeping in mind the freedom of the neck and the idea of lengthening the spine. Let the whole body come forward until the centre of gravity falls over the feet, that is to say, until the poise is such that if the chair were removed at this point, you would be left balanced in the position of a person performing the ” frog dance,” then, by the exercise of the muscles of the legs and back, straighten the legs at the hips, knees, and ankles, until the erect position is perfectly attained.” – pages 169-70

Later in the book, Alexander writes quite about the ideal position of the feet for standing, even including 2 sets of photographs to illustrate his description:

The Use of the Self – Chapter 1, Evolution of a Technique – 1955 reprinting

“Observation in the mirror showed me that when I was standing to recite I was using these other parts in certain wrong ways which synchronized with my wrong way of using my head and neck, larynx, vocal and breathing organs, and which involved a condition of undue muscle tension throughout my organism. I observed that this condition of undue muscle tension affected particularly the use of my legs, feet, and toes, my toes being contracted and bent downwards in such a way that my feet were unduly arched, my weight thrown more on to the outside of my feet than it should have been, and my balance interfered with.

“On discovering this, I thought back to see if I could account for it, and I recalled an instruction that had been given to me in the past by the late Mr. James Cathcart (at one time a member of Mr. Charles Kean’s Company) when I was taking lessons from him in dramatic expression and interpretation. Not being pleased with my way of standing and walking, he would say to me from time to time, ” Take hold of the floor with your feet.” He would then proceed to show me what he meant by this, and I did my best to copy him, believing that if I was told what to do to correct something that was wrong, I should be able to do it and all would be well. I persevered, and in time believed that my way of standing was now satisfactory, because I thought I was ” taking hold of the floor with my feet ” as I had seen him do.

“The belief is very generally held that if only we are told what to do in order to correct a wrong way of doing something, we can do it, and that if we feel we are doing it, all is well. All my experience, however, goes to show that this belief is a delusion.

“On recalling this experience I continued with the aid of mirrors to observe the use of myself more carefully than ever, and came to realize that what I was doing with my legs, feet, and toes when standing to recite was exerting a most harmful general influence upon the use of myself throughout my organism. This convinced me that the use of these parts involved an abnormal amount of muscle tension and was indirectly associated with my throat trouble, and I was strengthened in this conviction when I reminded myself that my teacher had found it necessary in the past to try to improve my way of standing in order to get better results in my reciting. It gradually dawned upon me that the wrong way I was using myself when I thought I was ” taking hold of the floor with my feet ” was the same wrong way I was using myself when in reciting I pulled my head back, depressed my larynx, etc., and that this wrong way of using myself constituted a combined wrong use of the whole of my physical-mental mechanisms. I then realized that this was the use which I habitually brought into play for all my activities, that it was what I may call the ” habitual use ” of myself, and that my desire to recite, like any other stimulus to activity, would inevitably cause this habitual wrong use to come into play and dominate any attempt I might be making to employ a better use of myself in reciting.” – pages 11,12

“It is important to remember that the use of a specific part in any activity is closely associated with the use of other parts of the organism, and that the influence exerted by the various parts one upon another is continuously changing in accordance with the manner of use of these parts. If a part directly employed in the activity is being used in a comparatively new way which is still unfamiliar, the stimulus to use this part in the new way is weak in comparison with the stimulus to use the other parts of the organism, which are being indirectly employed in the activity, in the old habitual way.

In the present case, an attempt was being made to bring about an unfamiliar use of the head and neck for the purpose of reciting. The stimulus to employ the new use of the head and neck was therefore bound to be weak as compared with the stimulus to employ the wrong habitual use of the feet and legs which had become familiar through being cultivated in the act of reciting.” – page 13

Three videos about the use of the feet: